A well-structured Veterinary Ordering Strategy directly impacts both of these, helping clinics improve efficiency, reduce waste, and optimize cash flow. This guide from Vetcelerator explores how to manage your veterinary ordering process strategically to keep costs in check and profitability growing.

The table of contents for what’s to come is as follows:

- Understanding Cost of Goods Sold: Misnomers and Measurement

- Benchmarking, Ratio Analysis, Pricing

- Ordering Strategy to Increase Cash Flow and Lower COGS

- Red Flags in your Cost of Goods

- Buying Groups

How to Create an Ordering Strategy For a Veterinary Clinic

How inventory is ordered can have a drastic impact on a clinic’s success. Developing a Veterinary Ordering Strategy helps you balance stock levels, maintain cash flow, and lower your overall COGS. Because using inventory makes money, carrying too many products or too much of a single product means that resources aren’t being used efficiently. This may feel uncomfortable at times, but if you’ve never had a day where you didn’t have the inventory item you needed, you are probably ordering too much inventory. A simple-to-use “rule of thumb” is that every item you order should be exhausted within 30 days.

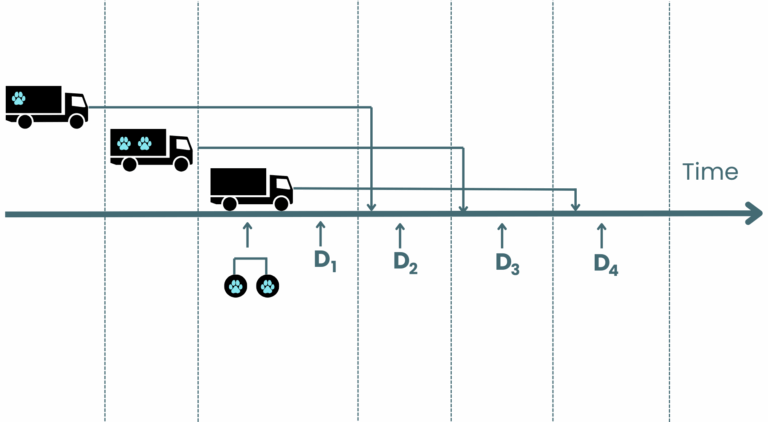

The hardest part of following the rule of thumb is “demand forecasting,” or knowing how much you should expect to use in the next period. Consider the following graphic in which:

- Periods represent days open

- Trucks represent inventory ordered, with arrows pointing to the expected delivery date

- D1, D2, D3, D4 represent the unknown demand for the items ordered on various days

- You place an order for items (trucks)

- It will arrive at some point in the future, usually two days

- Some demand (D1, D2, D3, D4) occurs before while you wait for additional items

- You have to do it all over again

So, your problem is you have to know how much you have, how much you will need, and how much you need to order.

There are a lot of unknowns. There is, of course, a lot of math behind how the smartest companies in the world stock their shelves. How we apply it to a veterinary clinic is part science and part art, because knowing what specific medications and how your clinic team manages their caseload is as important as the math that goes into proper ordering. What follows will be some generalities and some examples to illustrate how proper veterinary ordering for inventory management works.

Why a Veterinary Ordering Strategy Matters

A consistent Veterinary Ordering Strategy provides visibility into what’s on your shelves, what’s selling, and what needs to be restocked. This structure helps reduce overordering, prevents stockouts, and gives your team the confidence to manage inventory proactively.

Stock Control in Veterinary Clinics: The Foundation of a Good Veterinary Ordering Strategy

Every effective Veterinary Ordering Strategy starts with knowing what you already have on hand. Your PIMS can help you track this, even if it’s not perfect. Seems pretty straightforward. It’s hard to know how much you need if you don’t know how much your veterinary clinic has in stock. Unfortunately, across all the PIMS in the country, none of them have created a perfect system to help you with stock control in your clinic. Nonetheless, utilizing your PIMS can help you here.,

Many PIMS know how much you have in your veterinary practice based on how much you ordered and how much you dispensed via invoice. This works great with prescriptions and less so with inventory linked to procedures, such as vaccines and dewormers. Gold standard veterinary inventory management would use PIMS to do this work, track on-hand inventory, and set reorder points. This takes a lengthy setup and regular maintenance.

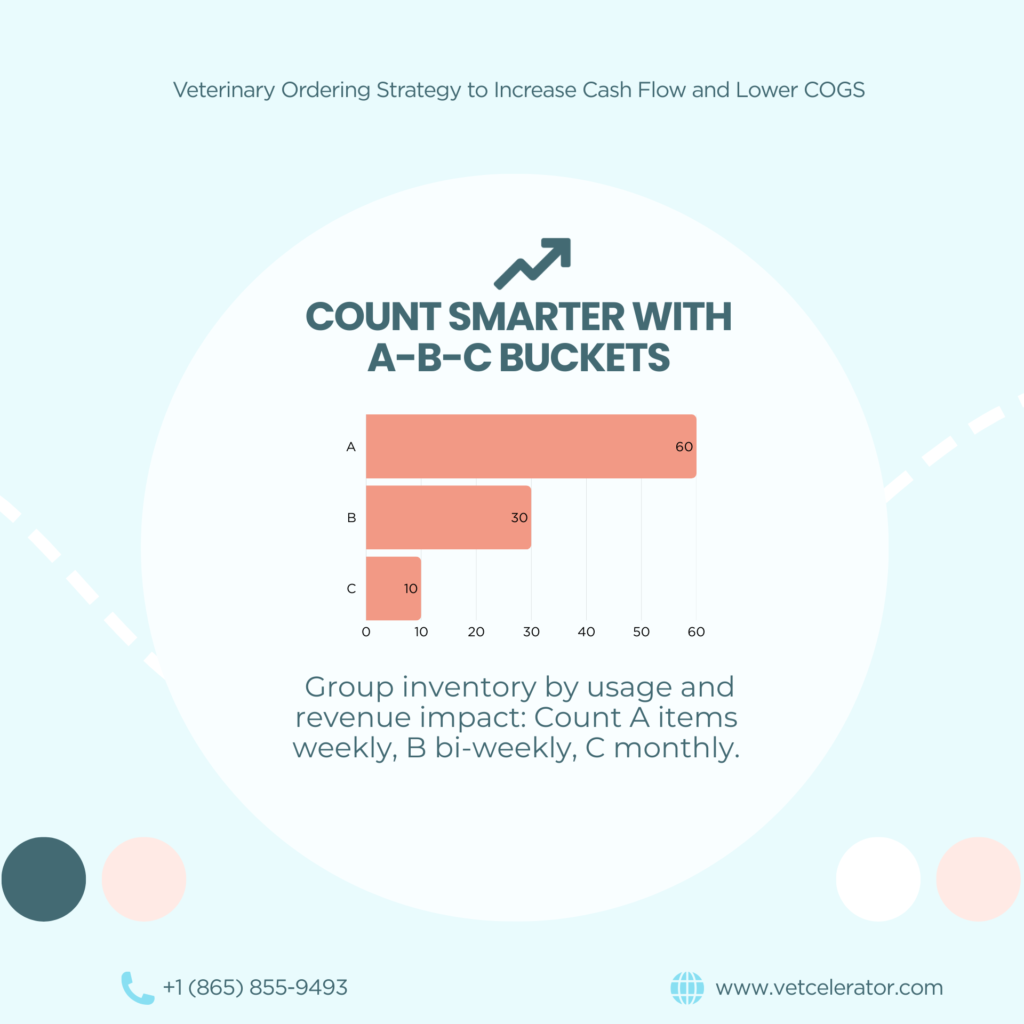

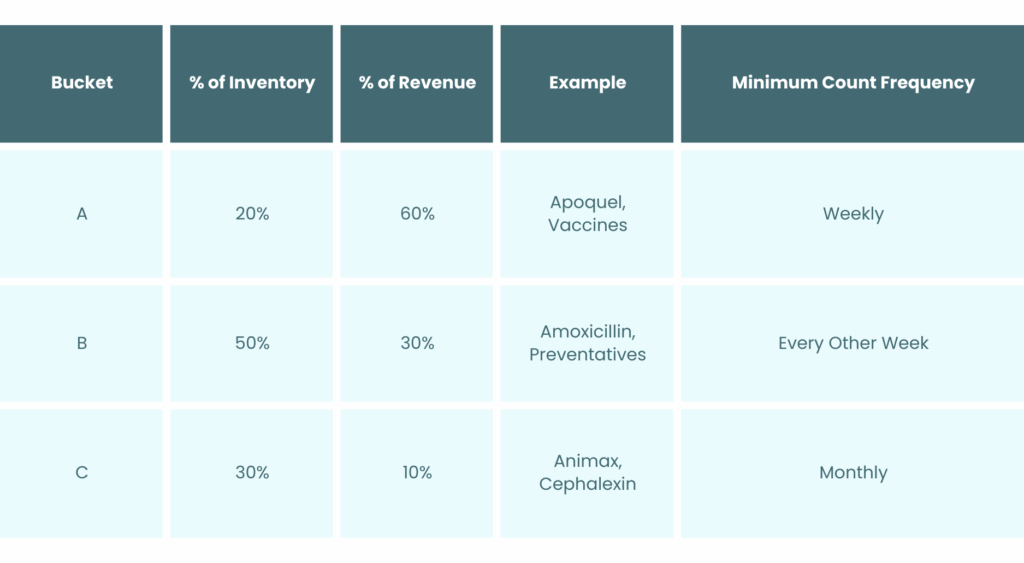

As a starting point, we at Vetcelerator propose the following. Separate your inventory, prescriptions, and vaccines into three buckets: A, B, and C.

This is a simpler starting point that will allow you to stay on top of your inventory from day one. “Minimum Count Frequency” would more traditionally be known as “cycle counts”.

Demand Forecasting: How Much You Will Need

Demand forecasting is at the heart of an efficient Veterinary Ordering Strategy. Understanding usage trends allows your clinic to order smarter and reduce waste.

The Complicated Way

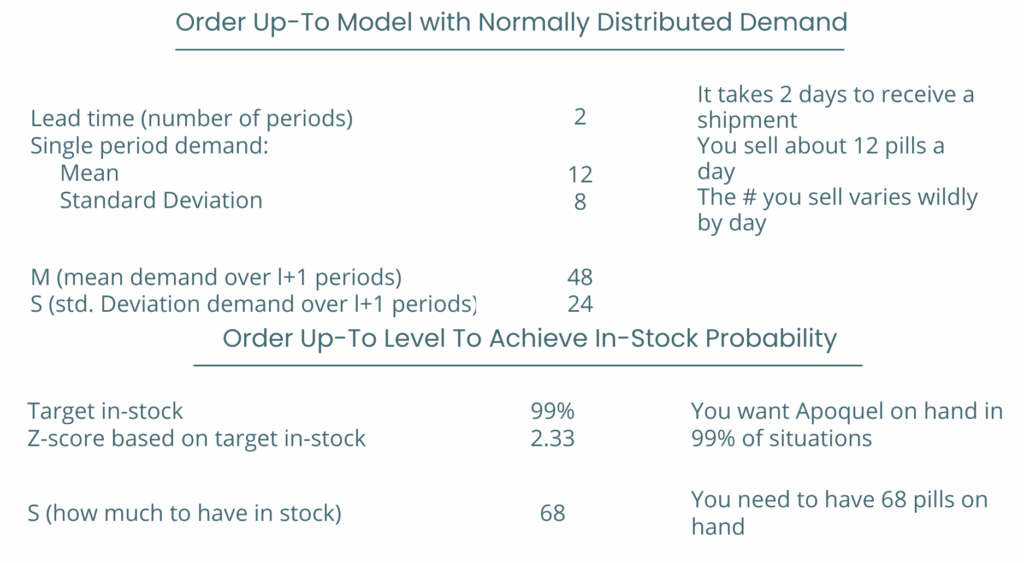

The complicated way would have us estimate mean demand, standard deviation, lead times, and in-stock probabilities and arrive at a reorder point.

Take the above example of a veterinary clinic that dispenses Apoquel. They use about 12 tablets a day, with a lot of variability around that demand. They can get a shipment in two days. Apoquel is important, and they always want to have it in stock. When we say “important,” we mean that the cost from a missed sale is generally greater than the cost of having too much. This is called the Critical Ratio in veterinary inventory management.

The complicated way suggests that this vet practice should count this item every week, and if there are fewer than around 68 tablets, they should order a bottle. This would be tough to do without technology, as the manual process would eat up too much administrative time.

The Simple Way

The simple way is this. Know how much you use roughly in a week. Keep track of this number. Then, if you have less than a two-week supply, order enough for a month. In the example above, two-week supply is roughly 120 tablets in the 16mg size. If you’re lower than 120 tablets, it’s time to order.

These would more traditionally be called “reorder points” or “reorder quantities.” Many PIMS allow veterinary clinics to set reorder points and match against usage. It’s a great practice, but even if you’re not using the PIMS, track this information somewhere. Keeping tabs on these numbers will help you understand how much you should have on the shelf and provides a consistent process that should prevent overordering.

Finally, if you find yourself in a situation with frequent shortages or overstock, it’s time to revisit the previous section on cycle counts.

Veterinary Inventory Management: Turning Your Veterinary Ordering Strategy into Action

Once you’ve forecasted demand, your Veterinary Ordering Strategy should determine how much and how often to order to balance availability and cash flow. You may be tempted to order the larger size. A bigger size saves you some cost, and maybe you don’t have to worry about ordering that drug for a while, so there is a mental relief. However, ordering the larger size means that the item sits on the shelf for longer, and you tie up the ordering budget with stuff you can’t use immediately. We would call this “Opportunity Cost.” There is also a literal “Carrying Cost” of the medication, but in most cases, that is trifling.

The Complicated Way

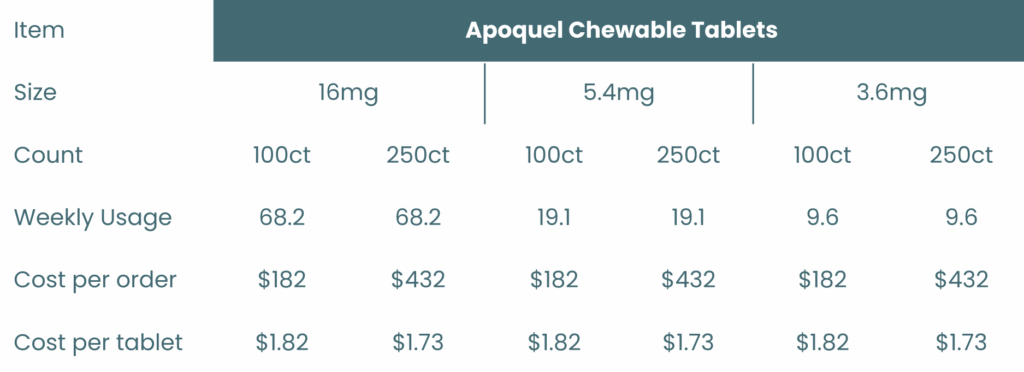

The complicated way would be for us to model out each item using weekly usage and determine if the cost savings from bulk purchases are offset by demand for effective inventory turnover.

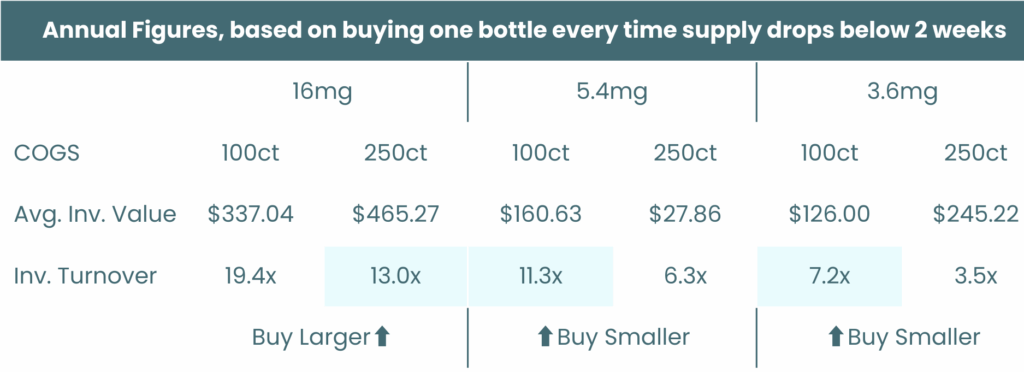

If we are trying to use up our entire supply of the order within the month, an inventory turnover should be around 12x. This says that the cost of the item is 12x the average inventory level. So, in the example above, we at Vetcelerator took three sizes (16, 5.4, and 3.6mg) and two counts (100, 250ct) of the common drug, Apoquel. We used the average demand for those sizes from a veterinary clinic we work with. The average weekly dispensing for the three sizes was 68.2, 19.1, and 9.6, respectively.

The results show that the smaller size is more efficient for the less used items, 5.4mg and 3.6mg. For the popular 16mg, the clinic uses enough to justify a larger size. For example, the smaller size of Apoquel will cost you an extra $22.75, but it may sit on the shelf anywhere from one to four months longer (except for the 16mg in this case).

The Simple Way

If the clinic has done a good job of knowing how much they use in a week, the simple way is… simple. When there is less than a two-week supply, order a month of supply. In the example above, you’d get the same result without needing to prove out the math of inventory turnover.

Use your ordering technology, whether Vetcove or others, to make sure you know what sizes are preferred for the items you regularly purchase. Be careful about promotions as they lead to a lot of cash flow tied up and damage overall effective inventory management for veterinary clinics.

Budgeting Efficiently for Veterinary Ordering

Budgeting is the backbone of a sound Veterinary Ordering Strategy. Setting weekly and monthly budgets allows veterinary clinics to align spending with production, keeping Cost of Goods Sold within target ranges.

Budgets that are too stringent can cause lost sales, e.g., you don’t buy something that you would have sold. Maintaining this balance is important, so think of budgets across two time horizons, weekly and monthly.

Balancing between the two is tricky. For example, if you have to order one or two sleeves of parasite preventatives instead of exactly what you need, then you are above budget. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t order, but you should have an approval process if you are over budget. Being over the weekly budget is generally more appropriate than being over a monthly budget.

Vetcove has a useful budgeting tool that is often underutilized by practices. When paired with inventory tracking, a defined Veterinary Ordering Strategy gives your team structure, accountability, and confidence in financial decision-making.

Weekly Budget

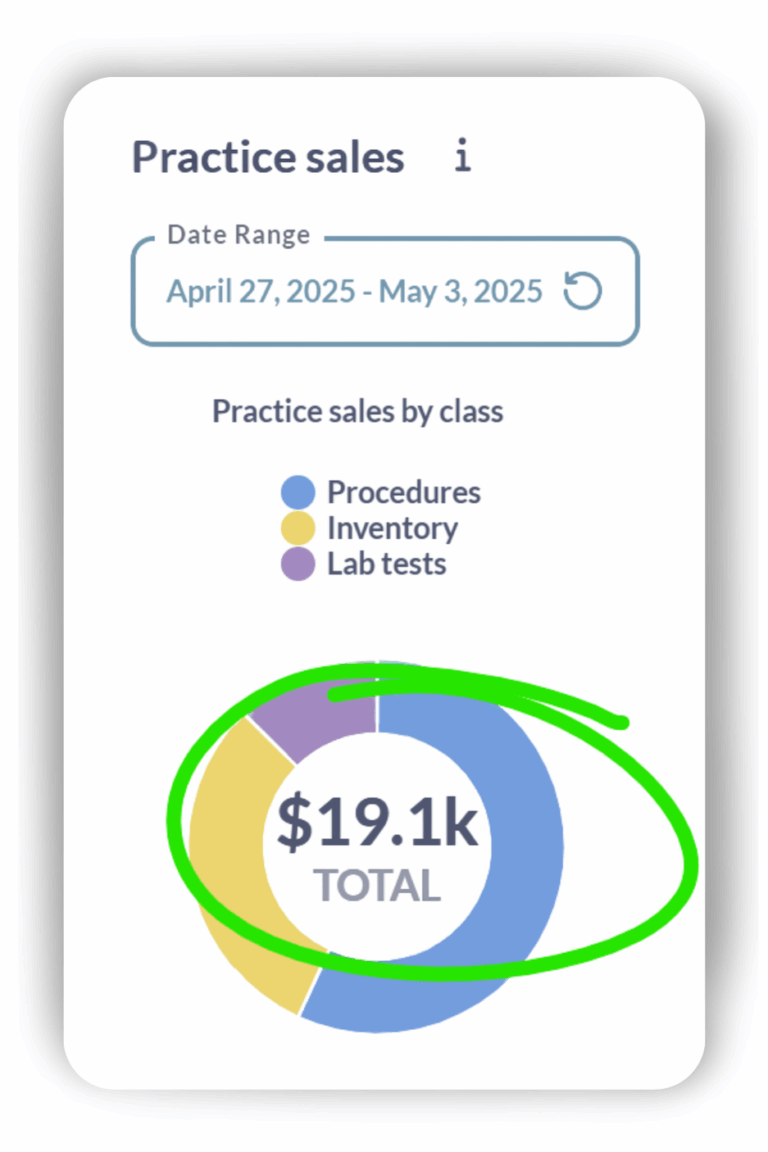

- Should be based on last week’s sales. At the end or the beginning of the week when you are prepping for your week ahead, get a report on last week’s production and take 15-20% of that number. A lower number is needed if the vet clinic uses a reference lab (because that isn’t “purchased” but is a component of COGS). That is your weekly budget.

- See the example from one practice management software. If the budget target is 15%, then the budget for next week is 19,100*15% = $2,865

Monthly Budget

- Should be set based on what the veterinary clinic is expected to produce in revenue that month. For example, if the clinic is expected to do $50,000 in sales in the next month, the budget should be 15% of $50,000 ($7,500).

- To determine what you think revenue should be, compare it to the prior month and the same month of the prior year.

Transparency in Veterinary COGS Management

One major issue we see in veterinary practices is anointing the leader of the cost of goods sold, but giving them zero transparency on expenses, financials, and benchmarks that we discussed previously.

So they are ultimately told “lower this number,” but they are not told how it’s generated, what influences it, and even whether or not they are successful. They are responsible for ordering, but not given a budget or not in charge of setting that budget. They are, however, in charge of setting the schedule, which is a ton of responsibility and even more expensive than COGS – so what’s the risk?

Does this sound familiar?

Conclusion

Getting started is the hardest part, but building a clear Veterinary Ordering Strategy can transform how your clinic manages inventory and cash flow. At Vetcelerator, we work with member clinics to design ordering systems that lower COGS, reduce waste, and improve profitability.

If you are a veterinary clinic that is struggling to get a handle on your ordering process and overall approach to managing Cost of Goods Sold, Check out our GPO Membership progam and start taking advange of savings today.